There are several versions of the origin of cards:

Chinese version

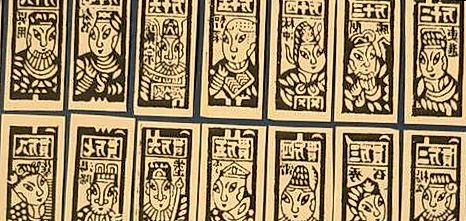

The first is Chinese, although many still do not believe it.

Chinese and Japanese cards are too unusual for us both in appearance and like the game, which is more similar to dominoes.

But there is no doubt that in the VIII century in China, first sticks and then strips of paper with different characters were used in the games.

These distant cards were also used instead of money, so they had three suits: a coin, two coins and many coins.

And in India, playing cards depicted the figure of a four-armed Shiva, who held a cup, a sword, a coin, and a rod.

Some believe that these symbols of the four Indian estates gave rise to the modern card suits.

Egyptian version

But much more popular is the Egyptian version of the origin of the cards, replicated by the latest occultists.

They claimed that Egyptian priests wrote down all the wisdom of the world in ancient times on 78 gold tablets, which were also depicted in the symbolic form of cards. 56 of them – the “Younger Arcanes” – became common playing cards, and the remaining 22 “Senior Arcanes” became part of the mysterious deck of the Tarot, used for divination.

This version was first promulgated in 1785 by the French occultist Etteila. His successors, Eliphas Levy and Dr. Papius and the Englishmen Mathers and Crowley, created their systems of interpreting the Tarot cards.

The name supposedly comes from the Egyptian “ta rosh” (“the way of kings”), and the cards themselves were brought to Europe either by Arabs or gypsies, who were often thought to be from Egypt.

However, no evidence of such an early existence of the Tarot deck has been found.

European version

Common cards appeared on the European continent no later than the 14th century according to the third version.

As early as 1367 in Bern, the card game was forbidden, and ten years later, a shocked papal envoy watched in horror as monks passionately played cards outside his cloister.

In 1392 Jacquemain Gringgonner, jester to the mentally ill King Charles VI of France, drew a card deck for his master’s amusement.

The then deck differed from the present one detail: it contained only 32 cards.

Four ladies were missing, the presence of which seemed excessive at the time.

It wasn’t until the next century that Italian artists began depicting Madonnas in paintings and on cards.

The 52 cards

There is speculation that the deck is not a random set of cards.

The 52 cards represent the number of weeks in the year, and the four suits represent the four seasons.

The green suit symbolizes energy and vitality, spring, west, water.

In medieval cards, the sign of the suit was depicted with a rod, staff, stick with green leaves, which is printing the cards were simplified to black spades.

The red suit symbolized beauty, north, spirituality. Cups, bowls, hearts, and books were depicted on the card of this suit.

The yellow suit symbolized intelligence, fire, south, business success.

A coin, a diamond, a lighted torch, the sun, fire, and gold bells were depicted on the playing card. The blue suit was a symbol of simplicity and decency. The sign of this suit was the acorn, crossed swords, and swords. Cards were 22 centimetres in length, making them extremely uncomfortable to play.

There was no uniformity in card suits.

In early Italian decks, they were called “swords,” “cups,” “denarii” (coins) and “rods.

It seems, as, in India, it was associated with the classes: nobility, clergy and merchant class, while the rod symbolized the royal power standing over them.

In the French version, swords became “spades”, cups became “hearts”, denarii became “diamonds”, and wands became “crosses” or “clubs” (the latter word in French means “cloverleaf”). In different languages, these names still sound differently; for example, in England and Germany, they are “spades,” “hearts,” “diamonds,” and “clubs,” while in Italy, they are “spears,” “hearts,” “squares,” and “flowers.

On German maps, one can still find the ancient names of the suits: “acorns,” “hearts,” “bells,” and “leaves.”

Cards and Arcanes

Early card games were quite complicated because in addition to the 56 standard cards, they used 22 “Senior Arcana” plus another 20 trump cards, named for the zodiac signs and the elements.

In different countries, these cards have other names and confused the rules so that the game was just impossible.

In addition, the cards were coloured by hand and cost so much that only the rich could buy them. Finally, in the 16th century, the cards became radically simplified – all except for the four “high suits” and the joker disappeared.

Interestingly, all card images had real or legendary prototypes. For example, the four kings are the greatest monarchs of antiquity: Charlemagne (hearts), the biblical King David (spades), Julius Caesar (diamonds) and Alexander the Great (clubs).

There was no unanimity about ladies – for example, the queen of hearts was Judith, Helen of Troy, or Didon.

The queen of spades was traditionally depicted as the goddess of war – Athena, Minerva and even Joan of Arc.

The biblical Rachel, after lengthy disputes, was chosen as queen of spades: she was perfect as the “queen of money” because she had robbed her father.

Finally, in early Italian cards as a virtuous Lucretia, the queen of clubs turned into Argyna, an allegory of vanity and vanity.

By the 13th century, cards were already known and famous throughout Europe.

From this point on, the history of the development of cards becomes clearer but rather monotonous. In the Middle Ages, both divination and gambling were considered sinful.

In addition, cards became the most popular game during the working day – a terrible sin, according to employers of all times and people.

So from the middle of the 13th century, the history of the development of cards turned into a history of related prohibitions.

For example, in seventeenth-century France, householders in whose apartments gambling card games were played paid fines, were deprived of civil rights and banished from town.

Card debts were not recognized by law, and parents could recover a large sum from a person who had won money from their child.

After the French Revolution, indirect taxes on the game were abolished, which stimulated its development.

Changed and the “pictures” – as kings were in disgrace, instead of them being accepted to draw geniuses, the ladies now symbolized the virtues – in other words, the new social structure came to the symbolism and cards.

True, as early as 1813, jacks, queens, and kings returned to cards. The indirect tax on playing cards was abolished in France only in 1945.